Enclosure of Common and Neoliberalism Policy

Thomas More’s Utopia, a text that was written in the 16th century, has summed up capitalism and the modern government under this system in just a quote: “What else is to be concluded from this but that you first make thieves and then punish them?” (More, 1516).

inherentIn the text, farmers and peasants were driven out of their land - their only means of livelihood - and reduced into beggars and thieves. These people were then punished by the government, often with moral justification. On the surface, this seems like a matter of common sense, of law and order; however, when one looks into the root cause and the concept of enclosure of commons, it reveals its essence: An interest contradiction between the workers and the capitalists.

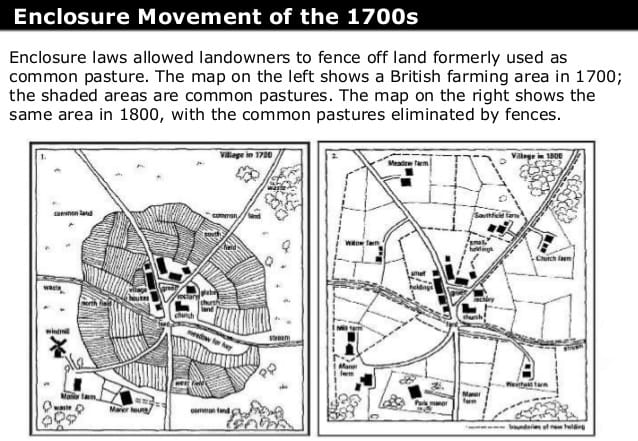

Enclosure of commons was a process where lands, resources, and natural surroundings shared among the People, then fenced off and claimed as private property belonging to corporations. In England, enclosures since the 16th century have displaced peasants from common lands, forcing them into either thieves, beggars, or wage labourers. Coincidentally, these newly proletarianized people, stripped of dignity and their means of production, started to concentrate in urban towns where factories needed cheap labour power.

Today, enclosure describes a broader process in which corporations, often with state support, seize control of shared resources such as forests, water, and mines. This process not only continues on settler-colonial lands stolen from Indigenous peoples but also extends deep into colonies and semi-colonies around the world. Resources that once sustained communities are measured in a grid-like system, commodified, and traded on the market like a piece of meat. The history, the culture, and the sense of community attached to the land are no longer recognized and cherished under the enclosure of common process.

In the 21st century, it’s easy to see how enclosures of commons have evolved into imperialism, defined as the highest stage of capitalism (Lenin, 1917). Capitalism, with its tendency to accumulate wealth, needs more markets to maximize the surplus value and dump the excess products. The imperialist powers colonized other countries and took control of their land and natural resources to extract them and ship them back to the West.

Resistance to these policies — such as efforts to nationalize oil fields in West Asia or mineral mines in Africa — has often been met with wars, coups, and devastating repression, resulting in millions of deaths. The underlying conflict has always been over who controls natural wealth: local governments attempting to develop their own countries, or foreign financial capital backed by imperialist states.

Domestically, the imperialist countries carried out neoliberalism (Harvey, 2005), a policy framework where necessities like housing and food were no longer funded by the government but by corporations and NGOs. It’s inhumane and immoral when the whole food production system, healthcare, or housing is controlled by a few corporations. The “trickle-down economy” is a blatant lie to the people. What neoliberalism has achieved is that it generates an enormous amount of wealth for the ruling class, pitting the workers against each other by scapegoating the immigrants as the reason why the job and housing market is crumbling down.

In conclusion, the enclosure of the commons, neoliberalism, and imperialism form a continuous historical process of dispossession. From the peasants expelled from their fields in More’s time to Palestinians being displaced since the Nakba of 1948 (Pappe, 2006) and now going through a genocide in Gaza, the story is the same: resources and wealth are concentrated in a few hands, while the many are left with poverty, precarity, and displacement. This process has been built on oppression, bloodshed, and exploitation — and has always been met with struggle and resistance.

Sources:

More, T. (1999). Utopia (R. M. Adams & G. B. Hutt, Trans.). W. W. Norton & Company. (Original work published 1516)

Lenin, V. I. (1964). Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism (S. W. Ryazanskaya, Trans.). International Publishers. (Original work published 1917)

Harvey, D. (2005). Neoliberalism as creative destruction. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 87(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2005.00101

Pappe, I. (2006). The ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Oneworld Publications.